INTRODUCTION

Let me begin with something that will probably disappoint most people who read this, I don’t believe that George Crum invented the potato chip. For a full discussion of that topic please see “Saratoga Springs, New York: Birthplace of the Potato Chip” and “Saratoga Potato Chip Stories: Traditions, Myths, and Legends.”

What George Crum was able to do was overcome a number of obstacles to become arguably one of the best known cooks in the country, in his own restaurant, in a community famous for its excesses at both the dining room table and gambling table. In 19th century America, this descendent of African, Native American and European ancestors, raised in poverty, unable to read or write, struggled for everything he gained. By the time he died in 1914 he had hosted Presidents, Senators, and the rich and famous at the restaurant he built, and his skills as a hunter fisherman and guide were almost as prized as his prowess as a chef. His story is interesting not only because of his unexpected success, but also because we know enough about his life to be able to see some of the highs and the lows he experienced. It also gives us a chance to see some details of the life of a man who wasn’t always famous and was never white. Too often the only time newspapers and histories written in the 19th century discussed a person of color the passage only dealt with a funny story, an eccentricity, or something that painted a picture of a character. There are articles like this about George Crum, but fortunately there is also coverage of his accomplishments. These materials when combined with information from official records create an unusually rich, although not complete story of his life. This is especially remarkable considering he was unable to leave a written record of what he thought and what he experienced.

GEORGE CRUM

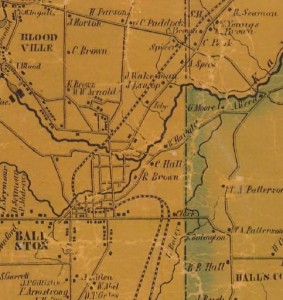

George was born on July 15, 1824 or 1825, in Saratoga County, New York. Sources not only disagree on the year of his birth, but also on his birthplace, although no one has suggested anywhere outside of Saratoga County, New York. [1] While it appears that George grew up in Ballston Spa, it’s possible that he was actually born in Saratoga Springs.[2] Growing up, George and his parents, Abraham Crum and Diana Tull were part of a small community of people of color in Ballston Spa.[3] I purposely have used the term people of color because using a term like black or African American may not be accurate or tell the entire story. It is very likely that at least some of the families in Ballston Spa that were identified by census takers as “other free persons” may have had ancestors of not only of African descent, but also European and possibly Native American. There is evidence to suggest George’s ancestors included people from Africa, Europe, and America before European discovery.[4]

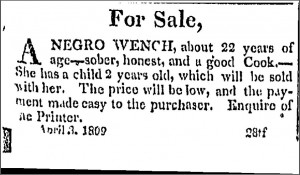

By the 1820s there were few slaves living in Ballston Spa, but there is a very good chance some of these residents were former slaves. Unfortunately freedom did not mean that these families, identified as other free persons, were treated the same as everyone else. Whatever their ancestry these residents of Ballston Spa, including the Crums, were viewed by white society as not white and society dealt with them using a different set of rules and laws.

Unfortunately we don’t even know how they viewed themselves or how they defined their community or communities. Many years later it is hard to know if these “other free persons” were one cohesive community or if there were divisions in how they saw and treated each other.

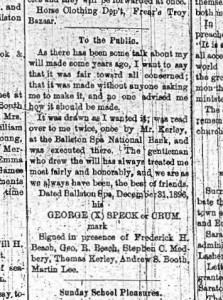

George Crum was one of only a few members of this community that had a chance to leave a record of how he viewed himself. Unfortunately he may not have been able to be completely honest; his ability to earn a living, his standing in the community and his pride may have influenced his choice of what was recorded. George’s chance came in his late 60s when he was successful enough to have a biographical sketch included in a history of Saratoga County. In order to have a biographical sketch included the book you paid for the privilege and in exchange you were able to control what was printed about you. What makes this kind of profile particularly interesting is that it is very likely that George provided the information to the book’s writers.[5]

George’s profile claimed that his father Abraham was of German descent and Diana, his mother, was “proud to claim that Indian blood flowed in her veins. “ He made no mention of anyone being of African descent on either side, and only acknowledged Native American roots on his mother’s side. However Diana is not identified as an Indian in any census, but is identified as both mulatto and black, suggesting that although she may have had Native American ancestors she also had African origins. [6] There are also records to suggest that Abraham had more than just German ancestors. Over his life Abraham was identified as a free colored person, black, mulatto and colored, and at least one account suggested that he may also have had some Native American ancestors.[7] We don’t know why George chose to ignore what seem to very likely be African ancestors. It is possible that by emphasizing Diana’s Native American ancestry and Abraham’s white ancestry George may have thought that his Native American heritage was an asset in his guiding and hunting business.

George was not the only member of his family who may have wanted to distance themselves from that portion of their past, his nephew George W. Francis took enough offense to a writer identifying his father Peter Francis as mulatto instead of an Indian that he wrote a letter to the newspaper to correct them.[8]

The information we have about George’s ancestry is a mix of conclusions made by people who identified George and his family based on how he looked and on the people around him. This happened in census and other official records and in newspaper stories printed during his lifetime. The words people used to describe him are very subjective, but may be useful when looked at over multiple years. For example one of the terms used to identify George was mulatto. When this term was used in the census it was meant to indicate anyone with any African ancestry combined with any other ancestry. When included in a description of a person it could also mean someone of African descent with light skin. A person described as a mulatto could have been of African descent, African and European descent, African and Native American descent, or even African, European, and Native American descent.

People of Native American descent were only supposed to be included in early censuses if they were living in or near white communities and not a part of tribe. In Federal censuses before 1870 it wasn’t even clear how an enumerator was supposed to identify these Indians, since that was not an option in the color column for Indian. Enumerators could have listed them as white, possibly mulatto or not at all.

All of this means that it is challenging to make any definitive conclusions about someone’s ancestry using the records we have at our disposal. To give a sense of how subjective ancestry may have been George was identified using the following terms during his life, Indian, half-breed, half Indian half negro, free colored person, mulatto, black, and colored.[9]

For George and other people of color these labels, whether they were accurate or not, carried weight. Applying those terms could affect how he and his family were treated, his civil rights, and his ability to earn a living. For his parents and grandparents it carried even more weight, it could mean the difference between enslavement and freedom.

Many people think that slavery existed only in the south, but people were enslaved in New York, including in Ballston Spa, Saratoga Springs, Albany, Schenectady, and communities in the Mohawk Valley, the areas where George’s family may have had its origins. While some of the Crums were free persons of color even before the Revolutionary War, not everyone was so fortunate; New Yorkers did not actually make an effort to end slavery in the state until 1799 and this gradual manumission was not completed until 1827. While I have not been able to document any enslaved ancestors in George’s family, it seems likely that at least some of George’s ancestors of African descent and even possibly his Native American ancestors were once slaves.

FAMILY ORIGINS

Tracing George’s ancestors has proven challenging but I have been able to make some connections back to 1776 and it is possible that some of his ancestors lived in New York State as early as the 17th century. [10] George’s paternal grandfather John Crum served in the Revolutionary War, enlisting while living in the Mohawk Valley on New York’s frontier.[11] Unfortunately his life before 1776 remains a mystery and I haven’t been able to discover anything about his parents.

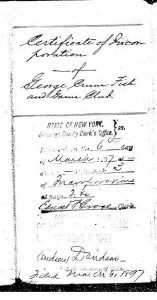

While it seems that George chose to use the name Speck in most of his formal or legal transactions he eventually became better known as George Crum. His grandfather used the name Crum or Crumb, but may not have used the name Speck.

Tracing the origins of a last name for a person of a color is particularly daunting. The names could have been passed from father to son or daughter, but it is also possible that a surname had been assigned or selected only recently. The choice of last name Crum or Speck, may have not always have been up to the family member; those who created the records may have made the choice for them. In the case of persons of color records often contained only first names and a descriptive phrase such as slave, free, Negro or Indian. For people with Native American ancestry surnames may have started to be used when they became Christians and for other persons of color when they gained freedom. It’s possible that the name Speck or Crum whether given or chosen came from the name of a slave owner, but it is also possible it was a nickname or a creation of some kind. There is also no way to know if Crum was just a variation of Speck or if Speck was a variation of Crum although it is easy to see the similarities in the name.

While there is no record of John Crum ever using the name Speck, George, his father Abraham, and George’s son Richard all used the name Crum as well as Speck during their lifetimes and it is possible that John Crum did that as well, it just hasn’t been captured in a surviving record.[12]

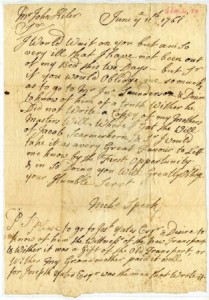

Letter from Nicholas Speck, Symon Speck’s son. From the collections of the Schenectady County Historical Society, Grems-Doolittle Library.

In my research I have discovered a number of families who are identified as persons of color in the records with the last name Speck, but almost no one with the last name Crum. I believe that John Crum was somehow related to the Speck’s who lived in Schenectady, New York, but have not been able to find that link. Several generations of Specks, both free and enslaved lived in Schenectady as early as 1705 and appear to be descended from Symon Speck and Susanna Thomassen. Their descendants remained in the area until the 1820s, but then seem to disappear with the exception possibly of George’s line.[13]

Hoping to find something about the origin of the Crum or Speck family I have researched families of European descent to search for any kind of connection, but I have not been able to discover anything. There were families of Dutch ancestry with the name Crum and families of German ancestry with the name Specht or Speck, but there are no obvious connections to John Crum.[14] I have not found any white Speck families in Saratoga, Schenectady, Albany, and Montgomery counties before the Revolutionary War and only one Crum, in that case Crom. I haven’t been able to find information about him other than he was a witness at the baptism of one of Symon Speck’s children.[15] Sanders, the last name of the man who once owned Symon Speck, the first member of the Speck family I have found, provides no clues to the origin of the Crum or Speck either.[16]

Symon Speck may have lived in Schenectady, but John Crum’s first records appear further to the West in the Mohawk River Valley. Before the Revolutionary War settlers had pushed from Albany and Schenectady West along the Mohawk River Valley and it is possible that some of Symon’s descendents were among them.

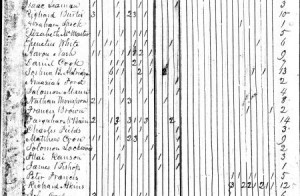

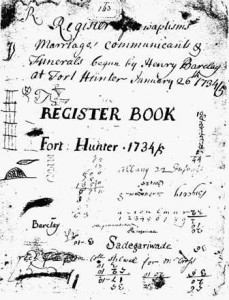

John Crum, George’s grandfather, was born about 1744, but we don’t know where.[17] In the late 1730s and early 1740s some Specks, very likely Symon Speck’s grandchildren, were baptized at a chapel at Fort Hunter, a military installation approximately twenty miles west of Schenectady. There is no mention of a John Speck or a John Crum, but it is possible that one of the children baptized there later used the name John or that his baptism either never occurred there or was just not recorded.[18]

The first time John Crum’s name appears in any record I have been able to find is on the muster roll of a Colonial militia unit in 1776.[19] By the 1770s there were settlements at Caughnawaga, now Fonda, Stone Arabia, and Herkimer on the North side of the river further west of Fort Hunter and Schenectady. Since militia units served in the region where they were raised, John was likely living in this area before he was mustered into the Rangers. John Crum served in Christopher Gettman’s Ranger Company of the Tryon County militia. Tryon County, was later renamed Montgomery County and covered a larger area than today’s Montgomery County, but an analysis of where the other rangers in his company lived suggests that his home was on the North side of the River, likely between Caughnawaga, now Fonda, and Stone Arabia.[20]

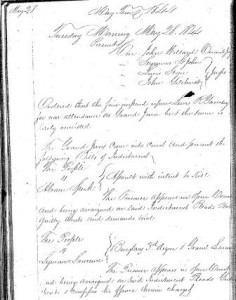

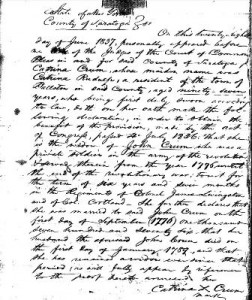

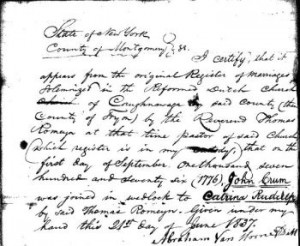

Affidavit from Abraham Van Horne regarding the marriage record of John Crum and Catrina Rudulp, from Catrina Crum’s pension application.

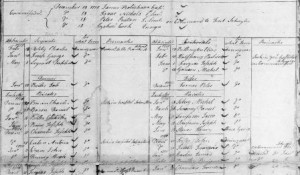

A few months after his name appeared on the militia rolls, in September 1776, John Crum married Catrina Rudulp, in the Reformed Protestant Dutch Church of Caughnawaga.[21] What is somewhat puzzling is that there is nothing in the record to indicate that either John or Catrina were persons of color. This could mean that John and Catrina were not persons of color or that the Church did not add that fact to their record. There are no indications that any of the marriages in the record involved people of color; however baptisms recorded at the same time do record that information. I believe, based on later census records, along with records relating to their descendants, that both John and Catrina were in fact people of color.[22] The fact that the marriage was performed at all and there was no mention of an owner in the record strongly suggests that they were free at the time of their marriage, although doesn’t necessarily mean that they had been born that way. The marriage occurred relatively late in their lives, John was approximately 32 years old and Catrina was about 36, which could indicated that it was a second marriage for one or both or that they may have waited to be married, perhaps waiting until they were free. Unfortunately I haven’t been able to discover anything about Catrina Rudulp Crum’s life before her marriage. I have not been able to find any other Rudulps or Rudolphs in area suggesting that Catrina could have been the first person in the family to use the last name Rudulp.

After a few months serving in the Ranger Company, and just days after his marriage, John joined the Continental Army at Johnstown, a community about four miles north of where John and Catrina were married.[23] During his service in Colonel James Livingston’s Regiment he fought at the Battle of Saratoga, and when stationed near West Point, his unit fired on the British Ship Vulture. This led to the capture of Major John Andre and the discovery of Benedict Arnold’s treason. [24] When Livingston’s regiment was disbanded, John Crum transferred to the 2nd New York and was present at Cornwallis’ surrender at the Battle of Yorktown.[25] Frost bite ended his service and forced his discharge from the army in 1782 as the War was coming to an end.[26] Unfortunately none of the records that would have indicated John’s ancestry have survived for his regiments. Only one type of record, the descriptive rolls contained physical information, most of the records do not indicate ancestry or color and because persons of color served in the same units and were paid the same as white soldiers, there are no clues in the surviving documents.

The Mohawk Valley frontier, where John and Catrina lived, had been devastated during the War and many people were either forced or chose to move back from the frontier to Schenectady or Albany. We don’t know if Catrina remained on the frontier during the War, moved to the relative safety of Albany or Schenectady, or travelled with the Army working in the camps doing laundry or cooking. Wherever Catrina lived during the War the Crums were among those to live in Albany after the War as early as 1784. [27] We don’t know how many children John and Catrina may have had, there are traces of two possibly three children, but only one baptism record survives. I have not been able to locate a record for Abraham, George’s father, who seems to have been born about 1789, but another, John Rudolff Crum was baptized in 1792 at the First Presbyterian Church in Albany.[28] This baptism records seems to be the only record he left, I haven’t been able to find any trace of John Rudolff Crum.

CATRINA CRUM

Catrina Crum recalled many years later that her husband died on January 1, 1789, but several other records suggest that he may have survived until the early 1790s. John Rudolph Crum’s baptism record specifically names him as the father, suggesting that he was alive until at least August of 1791.[29] After John Rudulff Crum’s baptism in 1792, the family disappears from records for the next two decades. There could be a number of explanations for this; it is possible they were missed in the 1800 and 1810 census. Or since both the 1800 and 1810 census only listed the head of a household they could have lived with other family members or friends, or worked as live- in servants in a white household.

About 1810 Catrina, and likely her son Abraham, moved to Ballston Spa, a Village about 30 miles north of Albany.[30] They weren’t the only people of color to move to Ballston Spa during that time period and it’s possible they all may have been attracted by the potential of employment.[31] Ballston Spa, even before Saratoga Springs, was a destination for wealthy visitors who sought to get out of northern cities in summer and to escape the heat of the south while sampling mineral waters that were widely believed to not only keep you healthy but cure disease. Only the very wealthiest Americans could visit these new resorts in Ballston Spa and Saratoga Springs, because they not only had the money to travel, they had the time. The Hotels built for these visitors required extensive staffs to serve their guests as they tried to keep them as comfortable and well fed as possible. These service jobs were some of the only ones that were open to people of color. Even those with a skill or an education found jobs they were qualified closed off to them because of discrimination. Catrina, although already in her 70s might have found work in a hotel kitchen or as a laundress, but the only job we know she had was not related to the Hotels. Catrina worked in the house of Thomas Palmer, an attorney, judge, and Saratoga County Clerk, probably taking care of his children. [32]

ABRAHAM CRUM

Abraham could possibly have found work as a waiter, a porter, or a hostler, but his options may have been more limited than other men of color. Abraham injured his back as a child and it left him disfigured and unable to perform some physically demanding jobs.[33] The injury apparently didn’t prevent him from racing horses at some point in his life, something that George Crum suggested he did well. He also worked as a laborer and a peddler, but his work history seems to have been somewhat sporadic.[34]

Abraham started a family with Diana Tull in the early 1820s. Unfortunately Diana’s background before her life with Abraham, like her mother in law Catrina’s before her life with John Crum, remains a mystery. The only information about her early life comes from George, through his 1893 profile. In that piece he suggested that at least some of her ancestors were members of the Stockbridge Tribe and that was where his Native American heritage came from. Diana’s last name Tull is very unusual and I have not been able to find any record associating it with the Stockbridge band of the Mohicans. It is of course possible that her father was not a Stockbridge and so the surname would not appear in tribal records. Her Stockbridge ancestors could have come from her mother side of the family and unfortunately we don’t know her surname. [35]

Diana was born between 1805 and 1809 in New York, possibly in Oneida County although the records conflict about the county.[36] By the time Diana was born the largest part of the Stockbridge tribe had relocated from the Massachusetts town that gave them their name to land given them by the Oneida Tribe in what is now Madison and Oneida County, New York.[37] While it’s possible that Diana’s family could have lived there, they could just have easily been a part of another community, white, Native American, or African American.[38]

As I covered earlier it seems that George Crum may have downplayed any African ancestors in his family. Because Diana was identified as either mulatto or black in census records I have included persons of color in my search for families with the Tull name. [39] I haven’t been able to find any Tull families, but there is a Toll family briefly mentioned in area records. Dinah Toll is listed in the 1820 census for the Town of Minden in Montgomery County. This Dinah, who was probably born at least 30 years before Abraham’s wife Diana, was living with three girls all under 14, one of whom could have been Diana Tull or Toll.[40]

GEORGE CRUM’S CHILDHOOD

I have been able to identify five of George’s siblings, but it is possible that there are more brothers or sisters that have left no records behind. The Crum children were George born in 1824 or 25, Mary born about 1828, Catharine born about 1830, Adelia born about 1834, Abraham Jr. born about 1836 and Diana born about 1838.[41]

We don’t know what kind of work Abraham did in the 1820’s 30’s and 40s, but it’s unlikely that horse racing was frequent enough or lucrative enough to make the family comfortable and feeding his family of at least eight had to present some financial challenges. Abraham’s record in the 1840 census suggests that he may not have been working at all.[42] The only other occupation, other than laborer, we know about, peddler, doesn’t seem to be something he did until after his children were grown.[43] Finding employment may not have been Abraham’s only problem, he made things even worse with frequent arrests. Beginning in 1830 Abraham was convicted of assault and battery almost a dozen times and we don’t know how many times he was arrested on other charges and not tried in the same courts. He spent time in jail and may have also have had to pay fines, both of which would seriously affect his ability to provide for his family.[44] Abraham’s last brush with the law was also the most serious. In 1844 he was convicted of assault with intent to kill and given a ten year sentence in the state prison at Ossining. [45]

We don’t know what was behind the unusual number of assault and battery convictions Abraham managed to rack up. We also don’t know if any of this aggression took place at home or if it was directed at family members. The few documents surviving from his trials do indicate that some members of his extended family were called as witnesses, but no one in his immediate family shows up.[46]

Abraham’s issues probably meant that the burden of providing fell to other members of the family, perhaps Diana took in wash, or worked in someone’s home or in one of the hotels as a servant or cook. Catrina Crum, George’s grandmother, who lived with the family, was eighty five when George was born, but still found a way to contribute. Beginning in 1837 Revolutionary War widows could apply for their husband’s pension and Catrina wasted no time in applying. Catrina’s application was approved and she received her first payment in 1839. It included a lump sum payment for the months that had passed since her application as well as her first quarterly payment. She used the windfall to purchase a piece of land, providing a home for her extended family.[47] The piece of property, too small to even warrant a measurement of area in the deed, was squeezed between the rail road tracks and the road leading to Saratoga Springs, outside the Village just south of Northline Road.

The struggle to provide for the family may have been the reason that George never learned to read or write. [48] George claimed to have attended the common schools of Ballston Spa and that is possible because persons of color apparently attended school with white students in Ballston Spa.[49] Like many poor families the Crum’s may have relied on their children working instead of attending school. This meant many children like George had to leave school at a young age, attend only a limited number of days, or never attend at all.

George’s financial contributions to the family may have started in the woods and lakes around their home hunting and fishing. Any food he could bring home was something that the family did not have to spend money on. Anything extra that George caught or shot could have been sold to neighbors or to one of Ballston Spa’s hotels. We don’t know if George developed his skills as a hunter and fisherman with the help of his father or if it was someone else.[50] It’s tempting to assume that George’s Native American Heritage gave him an affinity to hunting, but the fact is many young men would have spent time hunting and fishing. But unlike most of the boys and men who hunted and fished to provide for their families George seems to have had a natural talent for it, enough to make a living doing it.

OUT INTO THE WORLD

While he may have been able to contribute to the family George may not have realized he could make a living as a hunter and fisherman since he considered his first job to be as a laborer on a farm. While he may have been making money and helping to support the family with hunting and fishing as a younger man, it is more likely that George was in his mid-teens by the time he got the job on a farm.[51] He quickly discovered that life as a farm laborer did not suit him and he was able to convince the chef of the Sans Souci Hotel in Ballston Spa to hire him to provide the Hotel with fish and game. The chef may have already been an occasional customer for George’s fish and game and just saw the opportunity to guarantee a more stable source. [52]

The Sans Souci was anything but a typical small town hotel; it was built in 1805 to serve wealthy visitors to Ballston Spa and provided the kind of jobs that may have drawn Catrina Crum and other persons of color to Ballston Spa. It could accommodate over 150 visitors at a time, and when it was built, it was the largest resort hotel in the country.[53] For the hotel’s first two decades Ballston Spa and its springs were an even more fashionable destination than Saratoga Springs and for many of the rich and famous from around the United State and abroad, the Sans Souci was the place to stay. [54]

Although by the 1830s the San Souci’s and Ballston Spa’s glory days had passed numerous summer visitors still came to enjoy a quiet alternative to Saratoga Springs. [55] These guests still expected the same level of service and high quality meals served in Saratoga Springs hotels. One of the cooks at the Sans Souci at the time George started working may have been Peter Francis, although the exact years he worked there are unclear.[56] Francis, also a person of color, and a member of one of the other families that came to Ballston Spa before 1810, married George’s sister Mary about 1845.[57] He was older than George and may have worked for years before George became associated with the hotel.[58]

Whether it was an interest in cooking or a chance to make more money, George eventually secured a position as an assistant cook at the Hotel. This may have been where George first learned to cook, a skill he later refined around the campfire on hunting and fishing trips.[59] George’s time in the kitchen only lasted a few years and he left the employ of the Sans Souci in the early 1840s, probably before his younger sister Catharine started her career in the kitchen there.[60] George’s decision to leave cooking and go back to hunting and fishing may have been inspired by his brother in law, Peter Francis who left a successful career as a cook at the Sans Souci to pursue fishing and hunting, but to also to cook for his customers.[61]

Nothing was recorded at the time, but later accounts suggest that Pete Francis’ skill in preparing fish at the Sans Souci led one of his customers, James M. Cook to help him establish a home on Saratoga Lake where he acted as a guide for fishing parties and served the catch in his modest home. Peter was established there by 1842, perhaps earlier, although he returned to live and work in Ballston Spa at various times in the 1850s.[62]

There is no indication that George had the same kind of backing, or was ready to compete with Peter Francis, but he also moved to the Town of Malta to make a living as a hunter and fisherman. [63] But this time George provided fish and game to families and eventually to several hotels rather than to just one hotel. He expanded his business even further when he began acting as a guide on hunting and fishing trips organized by sportsmen who became his clients. [64]

Both George and Peter Francis chose Saratoga Lake as the base for their businesses and their homes. Located about five miles from Ballston Spa and four miles from Saratoga Springs, Saratoga Lake extends a little over five miles north to south and is about two and a half miles across at its widest point. Bordered on the West by the towns of Saratoga Springs and Malta and on the East by the towns Stillwater and Saratoga, the area around the lake was mostly unsettled and offered game such as woodcock, quail, partridge, deer and bear. The Lake itself and Kayaderosseras Creek, which empties into Saratoga Lake, supplied trout, black bass and other fish.

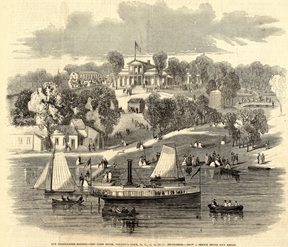

Saratoga Lake about 1850 with Snake Hill in the background and Moon’s dock to the right in the foreground.

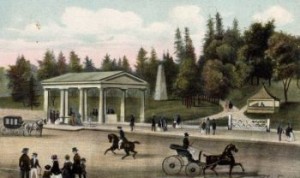

The Lake had become a popular destination for visitors to both Ballston Spa and Saratoga Springs who were searching for things to do while staying at the hotels in both villages. Lake Houses were established on the west and south sides of the Lake to cater to these visitors. These guests desired something to entertain them between their visits to the mineral springs, meals at the hotels and hops and entertainment in the evening. A drive or ride, usually taken in the afternoon, offered beautiful scenery and a chance to show off some of the visitor’s fine horses and elegant horse drawn vehicles. Entrepreneurs saw an opportunity and either opened their homes or built new structures to provide refreshment and entertainment for these visitors. These Lake Houses generally did not house overnight guests, but offered drinks and supplied boats, fishing gear, and even offered bowling alleys. Some visitors also took advantage of walking paths and places to rest and enjoy the scenery. The Lake Houses also served meals, preparing the fish visitors caught, either in the Lake or in stocked ponds or serving the fish and game provided by hunters and fisherman like George Crum.[65]

These fish and game dinners became the most profitable part of the Lake House businesses as the rich and famous tried to outdo each other by throwing lavish private parties. The parties were an attractive alternative for anyone who dreaded sitting down in one of Saratoga Spring’s huge hotels and dinning at common tables at the same time as hundreds of other guests, everyone else in the hotel.

Among the Lake Houses in business when George began his career on Saratoga Lake were Avery’s, Abel’s, Riley’s, Loomis’ and at least for a short time the White Sulphur Spring hotel. Lake Houses were likely George’s best customers requiring significant amounts of fresh game and fish to feed their visitors.[66]

GUIDING AND A NEW FAMILY

For some visitors and residents of Saratoga Springs the fish and game dinners were not exciting enough, they also wanted to experience hunting and fishing for themselves and would employ guides to facilitate their trips. In addition to finding fish and game guides often organized the equipment and supplies, set up camp and cooked whatever the party caught or shot during the day. These adventures ranged from day trips in the immediate area to longer trips into the Adirondacks, the wilderness to the north of Saratoga Springs. Many of the accounts of George Crum’s life refer to him as an Adirondack guide, but the Adirondack guides that become famous in the late 19th and early 20th century lived in the Adirondacks. It seems more likely that George just made occasional trips with hunting and fishing parties to the Adirondacks and lived and worked most of the time in the area around Saratoga Lake.[67]

Guides had to be able to find fish and game, but the most popular ones were also good cooks. We don’t know if George’s time at the Sans Souci was the only source of his culinary skills or if he had additional training. There are some accounts of a mysterious Frenchman in the woods in stories about George and it is also possible that his brother in law Peter Francis played a role in George’s training as a cook, especially if they worked together after they moved to the Town of Malta.[68]

Most customers at the Lake Houses and likely many of those that hired George as a guide were visitors to Saratoga Springs, and may have only been in town for the brief Saratoga summer season. But there were also wealthy local residents who visited the Lake Houses and hired guides, and their trips were not limited to the brief Saratoga summer season. The only two clients from George’s earliest days serving as a guide and mentioned in articles about George were Saratoga Springs residents. Thomas and George Clarke were the heirs of John Clarke, the man who created Congress Park in Saratoga Springs and made Saratoga Springs famous by bottling and shipping Congress Spring water around the country. [69]

During the early days of his hunting and guiding business George was living in the Town of Malta on Saratoga Lake in an area called Riley’s Cove. Phillip Riley opened a Lake House there in the 1820s and his widow Lydia and her sons continued to operate it until 1889.[70] George may have been drawn to this spot because Riley’s was a customer and may have offered access to potential customers for his guiding service. Whatever attracted him to the spot initially he must have enjoyed living there, with the exception of a brief move to another part of the Lake, George lived within a mile of the Cove the rest of his life.[71]

It was about this time that George started a family with Elizabeth Bennett. It doesn’t seem the couple was ever married, but they had three sons, William, Richard and George Jr., all born between 1846-1848.[72] Elizabeth or Betsey, the daughter of Peter and Abigail Wright Bennett, was born about 1828, probably in the Washington County New York. [73] The Bennett’s were Native Americans, members of the Stockbridge band of the Mohicans, the same tribe that George claimed as his mother Diana’s ancestry. The Bennett family’s links with the Stockbridge are better documented than Diana’s, their names appear on tribe censuses and some of the family, including Elizabeth, lived on reservation lands and were included on tribal rolls.[74]

Peter Bennett, Elizabeth’s father, may have been born in Stockbridge Massachusetts, and may have lived later with other members of the Stockbridge at New Stockbridge in Madison County, but it appears that at some point he moved to the Upper Hudson Valley with his family. At least two, possibly three of his children were born in Washington County, New York and it appears that the family may have spent most of the 1820s there.[75] By the time George and Elizabeth started their family most of the Stockbridge had moved to Wisconsin and most of Elizabeth’s family was living there by 1850.[76]

One of George Crum’s family members suggested many years later that George and Elizabeth may have met when the Bennetts came to Saratoga Springs to sell trinkets.[77] An Indian Encampment in Saratoga Springs was a popular attraction during the season. The encampment offered an opportunity for visitors to see Native American artisans who made baskets, beaded bags and other decorated items while demonstrating other aspects of Native American Life. The encampments continued for many years and opinions about the authenticity of both the offerings and the participants varied according to observers.[78] It’s not clear if members of the Stockbridge tribe regularly visited Saratoga Springs or participated in the encampments, but they did have a presence in the Saratoga Springs area at least one year. A reporter wrote the following during his visit to Saratoga Springs during the summer of 1846.

“We found several Indian families of the Stockbridge tribe bivouacked on the western shore, the women employed at their handiwork of basket-making, from which they derive quite a trade with visitors; the men were either employed at fishing, or lying listlessly about their tents. They appear to live entirely upon fish and roasting-ears, and are, in market phrase, in good condition.”[79]

It seems unlikely that the Bennetts would have travelled from Wisconsin to Saratoga Springs for only a few months to participate in encampments or to sell items to the tourists. It seems more likely that at least some of the family may have remained in New York.[80]

Some accounts suggest that George and his young family were struggling at Riley’s Cove; at least one person remembered some of the children being born in what he described as a shack.[81] These conditions may have led George to make a temporary move closer to another Lake House, one that served more visitors from Saratoga Springs than Riley’s. By September of 1850 George and his family lived about three miles further North on Saratoga Lake in the Town of Saratoga Springs. It is possible that they had lived there for a few years before the census was taken, there is just no record. The house they rented may still have been modest and they were sharing it with another family, but the Specks had enough money to own a pig and cow, suggesting that George’s fortunes may have started to improve. [82]

Instead of hunter or guide, at least according to the census enumerator, George’s primary job was taking care of horses at an inn or tavern. It seems likely that George was employed by Loomis’ Lake House, since George’s family was listed immediately after Loomis’ in the census and as the largest of the Lake House in the immediate area, was most likely to employ someone to take care of their customers horses.

Loomis’ Lake House stood on a bluff over Saratoga Lake on the road from Saratoga Springs to the Lake on the same land where James Green had operated a Lake House and a Ferry since the early 1800s.[83] Loomis’ served visitors from Saratoga Springs who made the five mile drive to the Lake and like other lake houses Loomis’ provided boats and fishing tackle, and served fish and game dinners featuring some apparently very special fried potatoes. For more about these potatoes and how they became the potato chips we know today see my article “Saratoga Springs, New York: Birthplace of the Potato Chip.”

The fact that the census said he worked with horses doesn’t mean that George didn’t also continue to fish, hunt, and possibly even serve as a guide. His time working for Loomis’ may have allowed him to come into contact with many of his future clients. Most positions at the Lake Houses were seasonal and it appears George may have moved back to Malta after the season ended, since they were back in the Town of Malta near Riley’s Cove by the end of 1851.[84]

A FAMILY FALLS APART

In late 1850 or early 1851 another member of the Bennett family, Elizabeth’s older sister Esther, came to live with the Crums. There are several accounts of what happened after Esther‘s arrival, but they were recorded almost sixty five years later and differ on some of the details. What they agree on is that eventually George married Esther Bennett and Elizabeth Bennett no longer lived with her family in Malta.[85]

Some of the stories suggested that George was not happy with the way that Elizabeth treated him and kicked her out, while others suggested that Elizabeth chose to leave after George married her sister.[86] We don’t know what Esther’s role in the breakup of the relationship was, active participant or innocent bystander, or what Esther’s relationship was with her sister Elizabeth after she left Malta. George’s relationship with Esther appears to have been more successful; they spent the rest of their lives together. [87]

There is some conflicting information about where Elizabeth went and who went with her when her relationship with George ended. One version suggests Elizabeth took an infant daughter and another refers to this fourth child as Owen.[88] If there was a fourth child he or she did not appear in the 1850 census and has not left any other trace of their presence. It is possible that Elizabeth actually took her youngest son George Jr. with her, at least temporarily. George’s nickname was apparently Noun, which may have been transformed over time and through recollection into Owen. The 1855 census indicates that George Jr. may have lived away from the family for about two years between late 1850 and 1852.[89]

All of the sources agree that Elizabeth went to join her family, but disagree on exactly where the family was living, possibly Missouri, Wisconsin or more generally “The West.” [90] It seems likely she went to join her parents Peter and Abigail Bennett in Calumet County, Wisconsin on a Stockbridge Reservation there.[91] Elizabeth did not stay single for long, by 1857 Elizabeth had a new man in her life, Cornelius Aaron, also a Stockbridge, and they had a child, the start of a new family.[92] They eventually moved, with other members of the tribe, to a Stockbridge community in Shawano County, Wisconsin, where Elizabeth died December 4, 1898.[93]

Esther Bennett , sometimes referred to in the records as Hester, was born in Salem, Washington County, New York on November 22, 1823 and was not only five years older than her sister, she was even a little older than George.[94] While it doesn’t appear that Elizabeth and George were ever married, at least some people believed that Esther and George were married.[95] George’s second relationship didn’t produce any children, but it lasted much longer, George and Esther lived together for over fifty years.

We can only imagine what kind of interesting family dynamics the breakup of George’s relationship with Elizabeth and the start of his life with Esther may have created in the Crum family. And those potential issues may have been why George’s son’s Richard and William were not living with him in 1855. Richard, only eight years old, was a live-in servant for one of George’s neighbors, Philip Riley and his family.[96] William, the oldest boy, was living with George’s parents on the family property north of the Village of Ballston Spa.[97]

There’s no sign that either of the boys lived with George and Esther again. In the years before the Civil War both boys worked on neighbor’s farms, likely working for board as well as wages.[98] Only the youngest son, George Jr. remained at home during this time.[99]

A LAND OWNER AND A CIVIL WAR

Over the next two decades of his life George continued the hunting and guiding businesses, but also established himself as a farmer and began to build his land holdings. It marked his transition from poor to comfortable as his businesses became more successful.

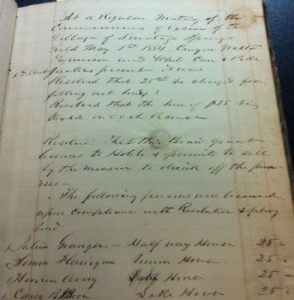

1854 record of Cary Moon’s license to sell alcohol at the Lake House. From the collection of Saratoga Springs City Historian.

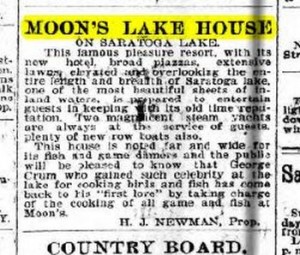

George’s may have benefited from changes to Saratoga Lake Houses. In 1854 Cary Moon and his wife Harriet purchased Loomis’ Lake House and renamed it Moon’s.[100] Moon referred to his predecessor as carrying on the business in a small way and it seems that Moon did make the Lake House even more of a destination for Saratoga Springs visitors and the local elite. [101]

Not only did Moon’s offer the traditional fish and game dinners and the chance to sail or row on the lake they added new attractions and improved existing offerings to bring out visitors. A bowling alley, paths, benches, and summer houses dotted the ten acre property. Small steam powered boats left the dock for tours of the Lake and stops at other Lake Houses. [102] Visitors who wanted light refreshment sat on the porches or at small tables on the grounds and were served drinks and the crispy fried potatoes that eventually became known as Saratoga chips. The casual visitors on the porches only supplemented the profits made from Moon’s elegant fish and game dinners and legendarily expensive private parties. Moon’s became the most popular of the Lake Houses, gained a national reputation, and proved to be substantial customer for George; he supplied Moon’s with fish and game for nineteen years.[103]

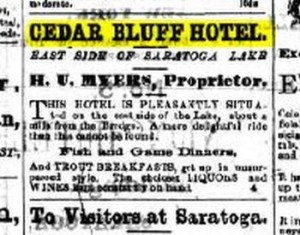

But Moon’s was not his only customer; George also supplied the Cedar Bluff Hotel on the East side of the Lake. Henry Myers’ Lake House opened in 1864 and soon became a rival of Moon’s as a destination for elaborate fish and game dinners and private parties.[104]

As a supplier to the two major Lake Houses, and perhaps others, George gained a reputation among the Lake House owners as a skilled hunter and fisherman, and the owners may have recommended George to their customers. And for the first time George’s prowess as a hunter and a fisherman spread by more than just word of mouth, his name started to appear in print. [105]

All of this may have helped him land guiding clients like John Cutler, a New York State Legislator, who operated a Livery Stable and Freight delivery business in Albany. Cutler shared an interest with many of Saratoga’s wealthy visitors, horse racing. He owned several of the most famous trotters of the time and was part of the trend setting social circles that not only visited Saratoga Springs and the Lake Houses, but had the time and money to hire a guide for an outing. [106]

In 1856 George was able to do something that many people, especially those of color could only dream of, he purchased a house and some land. George purchased two acres of land from John and Jane Masten for $170.[107] The land sat at the top of hill about a third of a mile from Saratoga Lake, overlooking the cove and Riley’s Lake House. George would have been very familiar with the property since it was located on the road between Riley’s Cove, his former home, and Saratoga Springs and Ballston Spa. The property was located in the hamlet of Malta Ridge a small farming community that sprung up around a tavern run by the Chase Family and by 1856 had its own Methodist Episcopal Church and School house.[108]

A few years after George purchased his land the country was rocked by the Civil War. The War changed the nature of visitors to Saratoga Springs, but it had a much more personal impact on many American families including the Crums. We don’t know how George felt about the War other than he identified himself as a Republican, suggesting that he supported it.[109] Although his eligibility for the draft might have been questioned, George was registered for it along with many other Saratoga county residents. [110] He was not selected to serve and he didn’t choose to volunteer, but two of his sons eventually joined the Union Army. How much influence George may have had on that decision is unclear since neither Richard nor William were living at home at the time they joined, but soldiers between 18 and 20 were required to get their parents’ permission to join. Although it is unlikely that this rule was always closely followed given the Army’s need for man power.

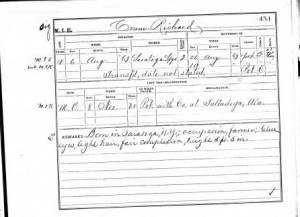

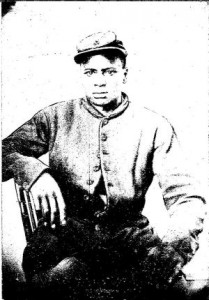

Richard was working on the Nelson Ramsdill farm, a short distance north of Riley’s Cove in the Town of Saratoga Springs, when he joined Company F of the New York 2nd Veteran Cavalry Regiment in June, 1863 under the name Richard Crum. [111]

There are two unusual things about Richard’s enlistment. The first is Richard’s age, without a birth or baptism record it is difficult to be sure of his age, but the best evidence suggests that Richard was 15 or 16 when he joined the Army, although his enlistment records his age as 18. That was the official minimum age for enlistment, but it is clear that this, like the need for a parent’s permission to join, was not strictly enforced. Secondly, the regiment that Richard joined was not a “colored” unit as they were designated at the time. At the beginning of the War people of color were generally not allowed to serve, but once they were able to enlist over two years into the War, they served in segregated units.

While there are other examples of people of color serving in white units during the Civil War it was relatively rare. [112] Richard was described in his later enlistment papers as having blue eyes, dark brown hair and fair complexion, suggesting that he could possibly have passed for white. [113] But in this case he would not have had much of a chance of success since the other soldiers in Company F were also from the Saratoga Springs area and could have known Richard and his family. [114] It may just have been something that did not matter to the men he served with and Richard may have joined a white unit, because the United States Colored Troop units had not been formed in New York when he joined the 2nd Veteran Cavalry.

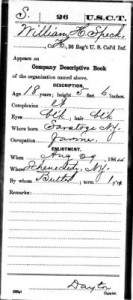

Eighteen year old William was also working as a farmer when he enlisted in the Union Army, but he enlisted as William Speck on August 29, 1864. He joined the 26th United States Colored Troops, Company H, one of the all African American units raised in New York State. William didn’t join when the 26th was first organized in February of 1864, but joined them after they were already stationed in the South for a term of one year. [115]

Both William and Richard survived the War and while they may have returned to the area it doesn’t appear they ever lived with George again. After the War Richard enlisted in the regular army, still in an all white unit, and served for over twenty seven years at various posts in the West.[116] William’s fate remains a mystery; the only trace I have been able to find of him, and it is only a possibility, is in Dodge County Wisconsin in 1880. [117]

While one account suggested that George Jr. also served in the Army I haven’t found any record and it seems unlikely since not only was he only 14 in 1865, he was listed as living at home at the time of the State Census in June 1865.[118] George Speck Jr., like his brother William seems to have disappeared after the Civil War.

Joseph Golden, born Cornelius Woodbeck, joined the 54th Massachusetts as James McNulty and eventually married Sarah Adkins, George Crum’s niece.

Given the chance, many of men of color eagerly volunteered to serve. William and Richard weren’t the only members of George Crum’s extended family who joined the Union Army. Among those that served were Esther and Elizabeth’s brother Peter Bennett, George’s brother in law George Johnson, and several of George’s nephews. [119]

While most of the people in George’s life survived the war, the family did not totally escape tragedy. His sister Catharine’s husband, Richard Adkins, died while serving in the Union Army.[120] The death of another soldier may have played a role in bringing Nancy Hagamore into the Crum’s lives.[121]

It’s not clear how Nancy came to live in the Crum household. She was listed as a boarder in the 1865 census even though she eventually was an employee. She doesn’t appear to have been related to George or Esther, but George’s extended family would have known her husband’s family. She was born Nancy Thompson on October 10, 1843 in Cobleskill a community in the Mohawk Valley to the Southwest of Saratoga County. By 1862 Nancy was living in Stillwater and had married George Hagamore a member of an established African American family from the Saratoga Springs area.[122]

George Hagamore, didn’t wait for New York State to form a regiment, he joined other African Americans who left Saratoga Springs and travelled to Rhode Island to join what became the 11th Regiment U. S. Colored Troops Heavy Artillery, one of the first African American Units to be formed in September, 1863. His service and his life were cut short when like many other soldiers during the war, including Richard Adkins, George Hagamore died from disease.[123]

George Hagamore’s death may have brought Nancy to the Crum household; although it is possible she lived there before George’s death. The relationship between George Crum and Nancy Hagamore has been the subject of a great deal of speculation, during their lifetimes and in the years after. She has been identified as a boarder, a servant, an employee, and often as part of a polygamous marriage with George and Esther.[124] Whatever the truth Nancy was an important part of George’s life and remained a part of his household until his death.[125]

The Civil War brought change to both Saratoga Springs and George’s businesses. An important attraction was added to Saratoga Springs during the Civil War; a thoroughbred race track was established. Wealthy men and women who already visited Saratoga had something else to do and the track attracted new groups to Saratoga Springs, those that loved sport and gambling. Gambling and the track become important parts of Saratoga Springs attraction. These new visitors provided another pool of potential clients for George’s guiding business and kept the Lake Houses busy, increasing their need for fish and game.

George business apparently remained good during the War since he was able to expand his property before the War ended. In 1864 he and Esther purchased ten acres of land across the road from his home, land that was more suitable for farming and gardening than his original purchase. [126] Not only does this suggest that George was making a success of his businesses, but it might have signaled a shift of some of his time away from the woods and lakes, for the now forty year old George.

George purchased more land in 1870, also presumably for farming. There were a couple of things that set this purchase apart from his earlier purchases of land. His first two pieces of land were just across the road from each other, but several farms and a road stood between George’s house and his new purchase.[127] Also apparently for the first time George borrowed money to make a land purchase.[128]

Even after this purchase George’s farm remained smaller than many of his neighbors, but he raised many of the same crops and kept much of the same livestock. The farm produced oats, potatoes, and apples, and he owned dairy cows, pigs, sheep and chickens. [129]

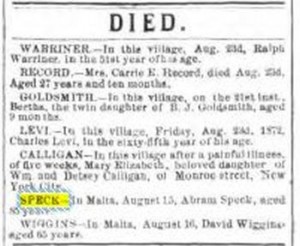

While records survive that give details of many aspects of George Crum’s life there isn’t much information about his relationship with his children, parents and siblings. His parent’s relationship included some separations, but we don’t know if it was caused by issues in the marriage or finances.[130] Abraham and Diana lived together for a time after Abraham’s pardon and release from prison, but appear to have separated after the 1860 sale of the land they inherited from George’s Grandmother, Catrina Crum.[131] Abraham lived with his son George at times in the years after the sale, but also lived on his own in the nearby Town of Milton.[132] He may have been living with George or possibly his daughter Mary Francis when he died in August of 1872 in the Town of Malta.[133]

Diana doesn’t seem to have ever lived with George and his family. After the sale of the Crum homestead she lived in Ballston Spa and her twenty six year old son Abraham lived with her.[134] By 1865 she had moved in with her daughter Mary Francis and her family in Malta. She passed away soon after in October, 1868.[135]

CATERER AND RESTAURANTEUR

Sometime during 1870s George added still another occupation to his growing list of business ventures, caterer. This new business may have started slowly and it may not have been something he did regularly, but George began to host and serve fish and game dinners at his home near Saratoga Lake. There may have been a variety of reasons for this change. George was facing his 50s, game was getting scarce, he had the resources of his growing farm at his disposal, and he may have been filling a void created by the death of Peter Francis.

In many ways the hotels and Lake Houses were victims of their own success by the 1870s since it was growing harder to find game in the area. Demand wasn’t just limited to the Lake Houses; hunters could sell their game birds at almost any rail road station to agents who supplied hotels and other eateries.[136] Longer trips to the Adirondacks were needed to supply the hotels and lake houses, but game was still plentiful enough for successful trips into the woods for small parties of hunters. This may have led the aging Crum to concentrate on guiding and preparing meals.

The scarcity of game may also have led George to become involved in conservation. George served as game constable for Malta. It was an elected office and George ran for it in 1873 and was elected several other times in the 1870s.[137] This apparently didn’t mean he was immune to the temptation of taking more than his limit though; he and his party were fined for violating game laws in the nearby town of Galway in 1880.[138]

At the same time George also increased his commitment to farming and began growing buckwheat and Indian corn in addition to his oats, potatoes and apples. He also had plenty of land for a market garden, but apparently didn’t sell much from it, possibly because he was using it to provide for his family and guests. While George’s farm was similar in many ways to his neighbors, just on a smaller scale, there were some differences. Almost all of George’s land was improved, and at least until the 1880s, the last year information is available, his holdings did not include timber land or wood lots and he did not sell firewood as most of his neighbors did. There are also signs by 1880 that he may have started to raise chickens on a larger scale, possibly to supply his catering business.[139]

Peter Francis, George’s brother in law, died in 1874 after years of serving visitors fish dinners at his small home on the south end of Saratoga Lake.[140] Years before George Crum gained fame as a cook and restaurant owner Peter Francis entertained Senators and Congressman. There were stories published about him in newspapers, Harpers Magazine, and in a book of local history, William Stone’s Reminiscences of Saratoga and Ballston. [141] The stories about Peter not only depicted him as a character, but also as a skilled fisherman, excellent guide, outstanding cook, and often emphasized his Native American ancestry. George Crum began to be described the same way.

We don’t know if George and Peter cooperated in business or saw each other as rivals. By the 1870s while George was on his way up, but Peter Francis and his family faced several setbacks. In 1871, Peter’s home and business were destroyed by fire and he had to rely on the support of the community to rebuild.[142] It took a few years to reopen and it’s not clear how successful his business was after the fire. Following Peter’s death his widow Mary tried to carry on the business, but she was not able to match Pete’s earlier success and the Francis family sold the property in 1878.[143]

In 1877 George received a brief mention as being responsible for the catering of a fish and game dinner at Riley’s Grove attended by a number of Ballston Spa residents. The fact that his name was even mentioned suggests that he had some fame as a cook.[144] It was a reputation he seems to have developed in the woods cooking over an open fire, while he guided parties on hunting and fishing trips. This mention in the paper may be the result of his transition from cooking in the woods into bringing the parties to his home. That move enabled him to serve more people, gave him as chance to make money beyond the limits of the hunting seasons and could have exposed his skills to more people, even those who edited newspapers.

One of the men who hired George as a guide and became a frequent visitor to Crum’s house was John McBride Davidson. Davidson owned the High Rock Spring Company in the 1870s and had homes in both Saratoga Springs and New York City.[145] He was an avid hunter and loved woodcock, often making arrangements so hunters brought him the first birds of every season. He also became a well known fisherman in Saratoga Springs.[146] These interests could have brought George Crum in contact with him, or they may have been introduced by one of Crum’s earlier clients, and Davidson’s friend, John Cutler.[147]

Davidson in turn appears to have introduced his circle of friends to George Crum’s skills as a guide and more importantly as a cook. Among his friends was William H. Vanderbilt, the oldest son and heir of Cornelius Vanderbilt.[148] A story written during George’s lifetime suggests that he won Vanderbilt’s admiration by preparing Vanderbilt’s favorite game bird, canvas back duck when no one else in Saratoga Springs could. Crum had never cooked them before, since they weren’t found near Saratoga Springs, but he managed to please Vanderbilt.[149]

Davidson had another circle of friends or perhaps more accurately associates from Tammany Hall and Boss Tweed’s infamous ring in New York City.[150] These politicians became another important circle of clients for George Crum. With Davidson, the politicians and Vanderbilt among his clients Crum’s prospects were better than ever. Not only would these men have provided plenty of business on their own, their patronage brought Crum to the attention of other wealthy clients and to newspapers.[151]

Top of the hill leading down to the spring and pond at the rear of George Crum’s property in the Town of Malta.

To better serve the guests at his home George made some changes to his property. He damned up a spring to create ponds for trout and bass, not only to make sure they were quickly available when he needed them, but also to make sure he could offer them when they were out of season.[152] Although the license application doesn’t survive George may also have gotten his first license allowing him to sell alcohol at this time.[153] While George continued to hunt and fish and may have still guided parties in the woods, he hired other hunters and fisherman to help fill his ponds and to provide him with game. [154]

There wasn’t enough room in George’s small house to feed his clients so the meals were served at the bottom of a hill below Crum’s house, near the spring that kept the wine cold and fed the fish ponds. George, Esther and Nancy all had a role in entertaining, George handled cooking the fish and game, Esther prepared the vegetables and Nancy supervised service and kept things running smoothly. [155]

While occasionally a woman may have joined in on these rustic excursions, the bulk of George’s customers would have been parties of men. Serving meals down the hill and away from the kitchen, slowed things down and may also have meant that food was served cold. Whether inspired by the demands of his clients for improved service or his own inspiration George decided that a better kitchen, a dining room and a bar would not only make everyone more comfortable it would also mean that George could serve more customers and could attract parties that contained women as well as men.

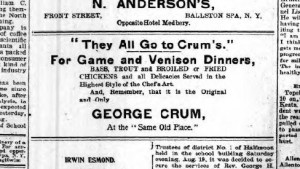

CRUM’S PLACE AND FAME

In the early 1880s George added a building between his house and steep hill and spring at the rear of his property.[156] It contained a kitchen at the rear, a dining room, and a barroom that could be separated from the dining room with a sliding door. There was a fourth room that was used as an additional dining room or as a waiting room.[157] French doors opened out onto porches that ran around most of the building and gave a view of the lake on one side. A coat of white paint and green shutters matched George’s house and above the door facing the road George mounted the head of an Elk, a present from Edward Kearney, one of Crum’s clients. Underneath the Elk was a simple sign that said Geo. Crum with a small fish symbol. [158] There sign didn’t say Crum’s Place, but that seems to be how, at least eventually, George referred to his business. It’s not clear if this started with visitors calling George’s home as Crum’s Place, before the new building was erected, or if the name may have come when the new building was opened.

Crum’s operated like many of the other Lake Houses; he hosted private parties, but also served fish and game dinners to walk-ins when private parties did not require all of Crum’s rooms. Crowds came to the Lake and Crum’s in the late afternoons for dinner and then returned to Saratoga Springs for the evening’s events and entertainment.[159] Some rode in their own impressive horse drawn vehicles, others hired equipment, and still others travelled as a group in chartered transportation such as a Tallyho coach or omnibus.[160] A new road opened in 1882 that trimmed the trip from Saratoga Springs to George’s place from seven miles down to four and a half miles making the ride even more attractive.[161]

When a group of customers arrived at Crum’s they would often be greeted by Nancy Hagamore or George Crum near the road.[162] They would take the order for the entire party from a very limited menu and only then allow visitors to walk past the house down a path through berry bushes and cherry trees toward Crum’s Place. If there was no wait it took about thirty minutes for the meal to be prepared, but since Crum’s could only hold about 30 people there often was a wait. At least in the beginning George had no problem making even the rich and powerful wait their turn if the restaurant was already full.[163]

While they waited patrons were offered champagne, wine or a whiskey cocktail and they could choose to wait in a small room decorated with fishing tackle or walk down the hill to the spring where they could rest on some old church pews arranged around the ponds. [164] And in a move that seems totally at odds with the rustic nature of the meals, for at least one season George employed a singer on Sunday’s to entertain his guests. [165]

Once inside Crum’s there were no individual tables for dinners, only two large tables surrounded by plain cane bottomed chairs.[166] Among the items served at different times were black bass and trout from the lake or George’s fish ponds, along with chicken, partridge, woodcock, and other game birds. The meals also included items from George’s farm in season; corn roasted on the charcoal range or boiled, Esther’s stewed potatoes, a salad of cucumbers, tomato and lettuce, and bread prepared by Nancy. [167] And at the end of the meal George offered fruit, almonds, cheese and coffee. [168]

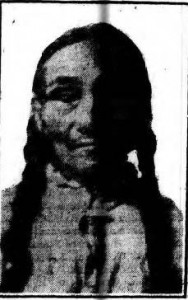

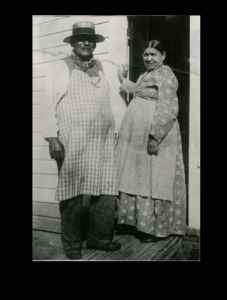

George and a woman I believe to be Esther Crum, probably at the backdoor of their house in Malta. c. 1890

Accustomed to cooking on a campfire with his guests all around him George may have tried to keep this experience alive by constructing a kitchen that opened onto one of the porches and allowed visitors to see what was going on in kitchen.[169] The simple kitchen contained a prep table across from the brick charcoal grill where he did all his cooking. On the back wall was a cooler that held all the fresh products for his dinners including the fish and game cleaned and prepared for the meals that day.[170]

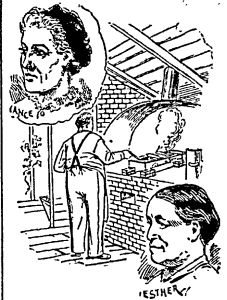

George Crum at work in his kitchen along with images of Nancy Hagamore and Esther Crum. New York Herald August 4, 1889.

While George and Nancy interacted with the guests, Esther remained in the house where only a few visitors were welcome. That was where she prepared the stewed potatoes and other vegetables for the meals. There is no indication that Saratoga Chips were ever served at Crum’s, but visitors did rave about the stewed potatoes both at Crum’s and when his protégé’s served them after Crum’s closed.[171]

The meals were not cheap; writers often suggested that the prices at Crum’s and Moon’s were comparable to those of New York City’s most elite restaurants. A meal without wine at Crum’s was $2, but most of the private parties ranged from $5 to $10 a plate when drinks and special requests were added.[172]

According to George it wasn’t the size of his restaurant that held him back it was the ongoing challenge of finding good game birds and enough servers.[173] Apparently George had mixed success in finding qualified servers, some patrons described them in unflattering terms and at other times were shocked to find well-educated college students serving their food.[174]

Not all of George’s customers came from Saratoga Springs; many Troy residents who summered in cottages in the Village of Round Lake in the southern part of the Town of Malta made the relatively short excursion to Crum’s during the summer season.[175] During the winters, horse races on frozen Saratoga Lake attracted horsemen from as far away as New York City, but George also entertained parties from Schenectady, Troy, Albany and Ballston Spa during the winters. Something he could not have easily done before he built Crum’s Place.[176]

Some stories written during George’s life suggested he was set up in business by William Vanderbilt or some of his other wealthy patrons.[177] While it’s possible they played a role, it appears that George financed most of the project on his own. He took out a mortgage on some of his land and raised $400, which may not have been enough to pay for everything, but would indicate he was an active participant. [178] It is possible the authors of these stories just underestimated George and assumed that he wasn’t capable of building his own business.

Even though George was serving some of the same people he once served around campfires at the bottom of the hill behind his house, newspapers did not seem to take notice of his visitors until he built his restaurant. The earliest mention I can find of Crum’s Place is in the New York Times of May 4, 1883 which suggested that that Crum’s and Moon’s were the place to go “for game and brook trout, and such rarities, which are too expensive for the general hotel table.”[179]

This was the first of dozens of items published in local and national newspapers, travel guides, and books about parties at Crum’s Place, George’s skills as a caterer, and profiles of George’s life. These articles ranged from brief mentions of someone hosting a party at Crum’s to substantial stories about George including illustrations.[180] While there are photographs and illustrations of George from this time some of these newspaper accounts give us additional information about George, although it is clear that the writers were often insensitive and inaccurate.

“The only indications of age are in his voice and in the thin, short gray whiskers on his chin. His step, once light and elastic, is heavy, but that is due to high living and the consequent avoirdupois that has overtaken him since he gave up the chase. His eye, though there is a good deal of Indian in it, is as soft as a gentle woman’s, and his voice is low and slow and very pleasing to the ear. Every remark is accompanied by a smile and punctuated with a little cough that lends to his speech a peculiar charm.

Though an Indian in appearance, Crum has both Spanish and German blood in his veins and there are times when the close observer can detect in him characteristics of the three races. He comes of the Stockbridge tribe.” [181]

“Crum, George is his front name (under the circumstances I can’t say Christian name) is an Indian, just a plain, unvarnished copper-colored, black-haired, black-eyed Indian, who wears baggy Jeans breeches, a hickory shirt, and an old straw hat; but instead of the tomahawk he wields the gridiron, and instead of scalps ‘round his ample waist he flourishes an apron.” [182]

George may have merited newspaper coverage for several reasons, the writers perceived George as a character, his clientele were the celebrities of the time, and they may have been curious why wealthy people would wait in line, dine in a rustic setting, and then rave about the abilities of the someone who did not conform to their idea of a typical chef.[183]

In many of the accounts his Native American ancestry and experience as a hunter, fisherman, and guide play a prominent role. This may have appealed to American’s fascination with nature and their often conflicting and confused image of Native Americans as both a “noble savage” and a terrible enemy. At the same time the Country’s army was fighting with tribes in the West, novels and the popular press also presented a romantic view of some of Native Americans. Many of the accounts also threw in a bit of scandal and perhaps what they saw as George’s refusal to follow the rules of society. They suggested that George shared his small home with not one, but two wives, referring to Esther and Nancy.[184]

While his background made him interesting, his patrons were probably the most important element in focusing the attention of newspapers on George. The tiny restaurant attracted some of the most wealthy and powerful men not just in New York but in the United States. Crum’s was very popular with politicians; he is said to have served three Presidents, Arthur, Grant, and Cleveland.[185] He was visited by Governors, United States Senators and Congressman representing a variety of States. Politicians from New York City including the men of Tammany Hall, the notoriously corrupt and powerful wing of the Democratic Party in the City also made use of Crum’s.[186]

Businessmen who came to Crum’s included William H. Vanderbilt who was a frequent visitor until his death in 1885, and others with a national reputation, such as Gould, Hill, Lorillard, Travers, Wall, Jerome, Whitney and Belmont, names that may only spark some recognition in Saratoga Springs today, but were national celebrities before the turn of the century.[187] A page could be filled with more of Crum’s wealthy patrons, but few of the names would be recognized today, even though at that time their actions were followed in society columns like Hollywood celebrities of today.

While notoriety may have given George’s business a boost, his success was built on his skills in the kitchen and by all accounts George Crum was an excellent cook. Perhaps the greatest testament to George’s skill as a cook was the patronage of local restaurateurs like Cary Moon, Edward Kearney, Albert Spencer and Charles Reed. Kearney succeeded Moon as one of the owners of Moon’s Lake House and Albert Spencer and Charles Reed succeeded John Morrissey as owners of the Clubhouse in Congress Park.[188] There are stories that credit George’s absolute control over the kitchen, his ability to get the best ingredients, attention to detail, and skill at his innovative and custom made charcoal grill, as the keys to his reputation as a chef. He reportedly never left anything to sit on his grill; he was constantly turning and basting, tamping and changing his fire, and rarely left the kitchen. Some stories called him the best cook in Saratoga, others the best cook in the country and recounted tales of famous restaurants like Delmonico’s trying to lure him to work in their kitchens. [189] George’s status as a cook became accepted enough that writers used him as a standard to compare other cooks to even after Crum’s closed. [190]

George was also respected because of his ability to obtain the best and freshest ingredients. He grew his own corn and picked it fresh when it was time to cook it. He raised fish in ponds on his property to insure freshness and availability, even when the fishing was restricted by game laws. As a former hunter and fisherman he had strong relationships with those that followed in his footsteps. He employed as many as seven hunters and five fishermen and even if hunters worked for other Lake Houses or agents he was able to get first choice from their daily hunts.[191] He also raised his own chickens to serve when game bird seasons were over ensuring that fresh fish and chicken dinners were always available.[192]

George also deserves some credit for being successful when other Lake businesses were not performing well. The 1880s, when George built his place, may not have been the best of the times for Saratoga Lake in general. People dreamed big in the 1870s when very popular rowing regattas were held on the Lake, but the dreams were not realized. Even new attractions like the Saratoga Lake Railroad and the huge steamer the Lady of the Lake were underutilized by the public.[193] Other Lake Houses were struggling, Cary Moon sold Moon’s Lake House in 1885 at a time when the nearly forty year old building was starting to deteriorate and business was falling away.[194] Promised improvements were not made by the new owners and Crum’s was able to capture much of the fish and game dinner business. By 1890 it was estimated that George Crum had two thirds of that business while Moon’s then run by Hiram Thomas and a new Lake House run by James H. Riley on Lake Lonely split the other third of the dinners.[195]

The presence of two James Riley’s in the Saratoga Springs area at the same time and in the same business makes for some confusing records. George’s friend and neighbor James Riley in Malta was the son of Phillip and Lydia Riley and ran the family’s nearly eighty year old Lake House.[196] The other, James H. Riley was famous as a regatta rower and a relative newcomer to serving visitors. His Lake House was located in the Town of Saratoga Springs a few miles to the north of Crum’s and Riley’s.[197] By 1889 James Riley was out of the Lake House business in Malta and James H. Riley’s business in Saratoga Springs was just starting to hit its stride.[198]

Crum’s neighbors the Riley’s operated a Lake House for over 80 years. Collection of Brookside Museum, Saratoga County Historical Society. c. 1899